Construction projects rarely follow the original script. Designs change, site conditions shift, and clients refine what they want while work is already in progress. Each change affects scope, cost, and time, which is why variation in construction needs a clear, controlled process rather than ad-hoc decisions.

This is where the variation order in construction comes in. A variation order formally records what is changing, why it is changing, how much it costs, and how it affects the schedule. Used properly, it turns inevitable change into something you can price, track, and enforce under the contract.

In this guide, we walk through what is variation in construction, what is variation order in construction project administration, how variation claims in construction fit into the picture, the main types of variation orders, the step-by-step process, valuation methods, and how to keep variations from becoming a constant source of disputes.

What Is Variation in Construction

“In construction, a variation is any change to the agreed scope of work after the contract has been signed, so the variation meaning in construction is simply ‘a change to what was originally contracted. It can involve adding, removing, or modifying parts of the works compared to what is shown in the drawings, specifications, or bill of quantities.

For example, if a client decides to upgrade standard floor tiles to higher-grade porcelain after construction has started, that change is treated as a variation to the original contract scope.

What Is a Variation Order in a Construction Project

When clients or contractors ask what is variation order in construction project terms is, the answer is simple: a variation order is a formal document issued under a construction contract to approve a change to the original scope of work, cost, or schedule

On a typical project, a variation order might be used to add extra parking spaces, change the façade material, or modify building services. Once signed by the required parties, it becomes part of the contract and provides a clear record that the change has been agreed upon.

What Are Variation Claims in Construction

Variation claims in construction are formal requests to adjust the contract price, time, or both because of a change in the agreed scope of work. They are closely linked to variation orders, but they are not the same thing.

A variation order records an approved change to the work. A variation claim is the contractor’s request to be compensated or given extra time for that change. In many contracts, the contractor first submits a variation claim with the description, reason, and cost/time impact. Once the parties agree on those impacts, the change is then documented through a signed variation order, which updates the contract.

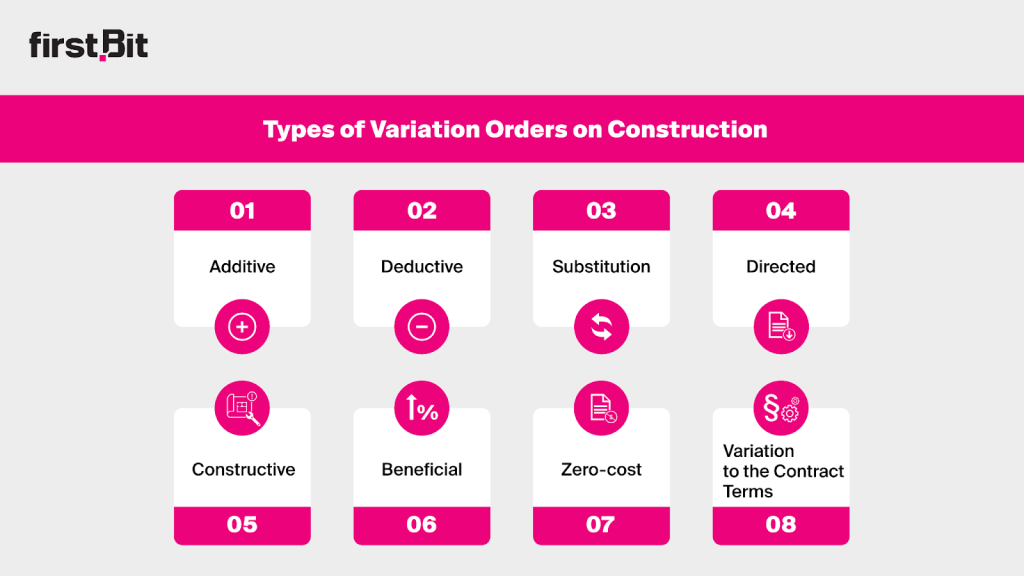

Types of Variation Orders on Construction

Not all variations affect a project in the same way. Some increase the scope of work, others reduce it, and some modify the materials, methods, or timing without changing overall quantities.

Types of construction variations

Classifying variation orders helps the project team understand their impact on scope, cost, and time, and makes it easier to price, approve, and track them under the contract.

Additive Variation Order in Construction

An additive variation order is a formal change that increases the scope, cost, or duration of a construction contract. It covers extra work that was not included in the original agreement, such as additional floors, upgraded finishes, or new building systems.

From a cost perspective, additive variations are often among the most expensive, because they bring in a completely new scope or higher specifications on top of what was originally priced. The later they are instructed, the more they tend to disrupt

procurement, sequencing, and preliminaries, which further amplifies their cost impact.

For example, if a client decides to add a rooftop terrace with extra MEP works after construction has started, this would be issued as an additive variation order. The contractor prices the new scope, the parties agree on the cost and any extension of time, and the variation is documented so the additional work can be delivered and paid for under clear, enforceable terms.

Deductive Variation Order in Construction

A deductive variation order is a formal change that removes or reduces part of the original scope of work and usually leads to a reduction in the contract sum. It is used when certain elements are no longer required, are simplified, or are scaled back, such as omitting a block of parking, reducing built-up area, or downgrading non-critical finishes.

However, research on variation orders shows that even “negative” changes can still create cost and time pressure

[?].

By the time a deductive variation is instructed, materials may already be procured, subcontract agreements signed, and work sequences locked in. Removing scope can trigger rework, disruptions to planned workflows, and claims for lost profit or idle resources. As a result, the net saving from a deductive variation is often smaller than the headline value of the deleted work.

Substitution Variation Order in Construction

A substitution variation order is a formal change that replaces one material, system, or construction method with another while keeping the underlying scope broadly the same. It often arises from material unavailability, new design preferences, or compliance requirements, such as changing façade cladding, MEP equipment, or internal finishes.

From a cost perspective, substitutions can move in both directions. On paper, they may look cost-neutral or even cost-saving, but the research on variation orders shows that secondary effects like rework, disruption, and logistics changes often add hidden cost. For example, switching to a different façade system late in the program can require revised shop drawings, new fixing details, and resequenced site work, which may increase overall project cost even if the new material itself is not more expensive.

Directed Variation Order in Construction

A directed variation order is a change formally instructed by the client, employer, or their representative under the contract. It clearly states what must be changed, added, or removed, and authorizes the contractor to proceed on that revised basis.

These variations are usually better documented and easier to enforce, but they can still have a high cost and time impact, especially when issued late in the program. Extra work, resequencing, and logistics changes often lead to increased project cost and delays, even when the instruction itself looks straightforward on paper.

Constructive Variation Order in Construction

A constructive variation order arises when the contractor has to change the work because of design errors, omissions, unclear documents, or unforeseen site conditions, even if there was no formal written instruction at the start. In practice, the contractor is “forced” to depart from the original scope to keep the project moving.

These variations are often among the most disruptive and expensive. They tend to lead to rework, inefficient sequencing, and additional supervision and coordination on site. Because there is no clear initial instruction, constructive variations also carry a higher risk of dispute: the contractor must prove that the change was necessary, that it was caused by design or latent conditions, and that the extra cost and time are justified under the contract.

Beneficial Variation Order in Construction

A beneficial variation order is a change that improves the project’s cost, time, or performance outcomes compared to the original design. It is usually initiated by the contractor or consultant as a form of value engineering, such as proposing more efficient structural systems, alternative materials, or simplified details that still meet the required standards.

While the immediate goal is to reduce cost or shorten the schedule, the real benefit is often in lowering future risk. Well-designed beneficial variations can cut down on rework, simplify construction logistics, and make site operations more efficient. To avoid disputes later, the agreed savings, scope adjustments, and any shared benefits should be clearly documented in the variation order.

Zero-cost Variation Order in Construction

A zero-cost variation order is a formal change that does not directly alter the contract sum but still modifies the works, specifications, or schedule. It is used when the parties agree that the change has no immediate cost impact, for example, switching colors within the same product range, relocating minor non-structural elements, or adjusting details that can be built within existing allowances.

Even when the price stays the same, zero-cost variations should not be treated as informal tweaks. They can still affect coordination, sequencing, or future maintenance. Documenting them through a variation order keeps the record consistent, protects both parties if later claims arise, and ensures that as-built information reflects what was actually delivered on site.

Variation to the Contract Terms

A variation to the contract terms is a formal change that adjusts the legal or commercial conditions of the agreement, rather than the physical scope of work. It can modify clauses on time bars, payment terms, pricing methodology, risk allocation, or procedures for notices and approvals.

These changes are usually recorded through a contract amendment or a specially worded variation order. Because they affect how all future variations, claims, and payments are handled, they carry significant legal weight.

For example, the parties may agree to change from fixed rates to remeasurement for certain trades, or extend notice periods for variation claims. Any such adjustment should be clearly drafted, signed by authorized representatives, and cross-referenced to the main contract so there is no doubt about which terms now apply.

Stay ahead of delays

Monitor project progress with FirstBit

Request a demo

Causes and Triggers of Variation in Construction

Variations rarely happen “out of nowhere”. They usually trace back to a small set of recurring causes that affect scope, design, or site conditions. Understanding these triggers helps project teams plan contingencies and respond in a structured way when change is unavoidable.

Client-initiated Changes

Design upgrades, finish upgrades, layout revisions, or additional scope requested after the contract is signed. These are common in high-end residential, hospitality, and mixed-use projects where preferences evolve during construction.

Design Errors or Omissions

Incomplete drawings, missing details, clashes between disciplines, or inconsistent specifications. Gaps in design information often show up only once work starts, forcing rework and scope adjustments.

Unforeseen Site Conditions

Latent ground conditions, such as rock, weak soil, groundwater, or hidden utilities that were not identified in surveys. These conditions can require additional excavation, protection, or redesign.

Regulatory or Code Changes

New or updated building codes, fire safety rules, green building requirements, or authority comments during review. Compliance with revised regulations can demand changes to systems, materials, or layouts.

Material or Equipment Shortages

Supply chain disruptions, long lead times, embargoes, or price spikes make originally specified products unavailable or impractical. Substitutions or alternative systems often trigger formal variations.

Contractual Ambiguity or Incomplete Documents

Vague specifications, unclear scope definitions, or conflicting contract clauses. Different interpretations between the client, consultant, and contractor frequently lead to scope disputes and variation orders.

Delays in Approvals or Permits

Slow responses from authorities, late design approvals, or bottlenecks in shop drawing and submittal reviews. To recover time, the team may resequence work or accelerate activities through variations.

Contractor or Subcontractor Performance Issues

Financial instability, poor workmanship, or capacity constraints at the contractor or subcontractor level. Replacement of trades, corrective work, or revised construction methods can all result in additional variations.

Variation Order Process: Step by Step

A variation order is a controlled process. A change is first identified, then notified, priced, reviewed, and either approved or rejected before it is implemented on site and reflected in the contract sum and program.

Clear stages make it easier to prove entitlement, avoid informal instructions, and keep cost and time impacts visible to all parties. The subsections below break this process down step by step.

1. Identification of a Potential Variation

Identification of a potential variation is the moment someone on the project realizes that the works need to change compared to the original contract documents. This can happen because of:

All of these can be noticed during design reviews, coordination meetings, or on-site.

What to do

As soon as a change is spotted, record what has changed, where it appears in the drawings or specifications, who raised it, and when it was discovered. Flag it internally as a potential variation, notify the project manager or quantity surveyor, and make sure no irreversible work proceeds until the impact on scope, cost, and time has been checked against the contract.

2. Formal Notification

Formal notification is the step where the contractor (or sometimes the consultant) gives written notice that a potential change may be a variation under the contract. It links the issue to the relevant contract clause and starts the clock on any notice period, which is critical under

FIDIC-style and

GCC contracts.

What to do

Issue a written notice as soon as the change is identified, within the time limit set by the contract. Refer to the contract number, variation or claim clause, describe the event briefly, note the date it occurred, and state that cost and/or time impacts will follow in a separate submission. Send it through the agreed channel (e.g., email or ERP system) and keep a copy in the variation log.

3. Submission of Variation Request

Submission of a variation request is where the contractor turns the potential change into a formal proposal with a defined scope, cost, and time impact. It takes the initial notice and develops it into a complete package that the client or engineer can assess and approve.

What to do

Prepare a written variation request that clearly describes the change, why it is required, and which drawings or specs it affects. Attach a cost breakdown (labor, materials, plant, preliminaries, mark-up) and a statement on any program impact, including whether an Extension of Time is needed.

Reference the relevant contract clauses, previous instructions or RFIs, and include supporting documents such as revised drawings, supplier quotations, or method statements. Submit it through the formal contract channel and record it in the variation register with date, value, and status.

4. Review and Evaluation

Review and evaluation is the stage where the proposed variation is tested for validity, cost, and time impact before anyone commits. The contractor, consultant, and client (or engineer) assess whether the change is necessary, reasonable, and compliant with the contract.

What to do

The evaluating party (often the consultant QS or engineer) should check that the variation falls within the contract scope, is properly notified, and references the correct clauses. Verify quantities, unit rates, preliminaries, and any daywork against the contract and BOQ. Assess the schedule impact and any claimed Extension of Time, checking logic against the current program.

Request clarifications or revisions where costs, assumptions, or methods are unclear, and document all comments, negotiations, and provisional agreements in the variation log before moving to approval or rejection.

5. Approval or Rejection of the Variation

Approval or rejection is when the client or engineer issues a clear decision on the proposed change. Based on the evaluation, they either accept the scope, price, and time impact, ask for adjustments, or formally reject the variation.

What to do

The approving party should issue a written decision that clearly states “approved,” “approved with modifications,” or “rejected,” and reference the variation number and contract clause.

If approved, confirm the final cost, any Extension of Time, and conditions (for example, updated drawings required before work starts).

If rejected, give brief reasons and keep all correspondence, comments, and revised offers attached to the same variation record so the decision trail is easy to follow later.

6. Formal Variation Order Format in Construction

This step turns the agreed change into a formal document that becomes part of the contract record. The variation is set out in a standard format so scope, cost, and time changes are easy to read, reference, and enforce.

What to do

Issue a written variation order on the agreed template, including: project and contract details, unique variation number, clear description of the change, reason for the variation, cost breakdown, confirmed time impact (including any EOT), and required approvals/signatures.

A consistent variation order format in construction makes it much easier for both parties to review, approve, and audit changes.

Attach all supporting documents (revised drawings, specs, quotations, correspondence) and circulate the signed variation order to the contractor, consultant, and site team before any related work starts.

7. Implementation of the Approved Variation

Once a variation is approved, it has to be built into the live project, not left as a paper change. This is where drawings, schedules, and site activities are updated so the team actually delivers the revised scope.

What to do

Issue updated drawings and instructions with the variation reference number, revise the schedule and procurement logs, and brief site and subcontractor teams so they all work from the same, current version of the scope.

8. Payment and Cost/Time Adjustment

This step translates an approved variation into money and time by adjusting the contract sum and, where justified, the completion date. The valuation method in the contract is applied, the variation is added to the payment process, and any agreed extension of time is reflected in the project schedule.

What to do

Update the contract sum and schedule using the approved variation value and time impact, link the variation to the schedule of values, and include it in the next progress claim. Make sure any extension of time, preliminaries, and indirect costs are clearly documented so they can be defended if questioned later.

9. Documentation and Record-Keeping

This step is about keeping a clean, complete record of every variation from first notice to final payment. All correspondence, approvals, drawings, and cost details are organized so anyone can trace what changed, why it changed, and how it was valued.

What to do

Maintain a central variation register with unique numbers, status (proposed, approved, rejected, pending), and values. File emails, notices, quotes, drawings, and signed orders under the same reference, and keep versions of revised documents clearly labeled.

Project management or ERP software can make this much easier by storing all variation data in one place and linking it to costs and schedules. This creates an audit trail that supports payment claims, protects against disputes, and keeps the commercial history of the project transparent.

Keep projects running like clockwork

Request a demo

Valuation Methods for a Variation in Construction

Once a variation is agreed in principle, the next question is simple: how much is it worth and what does it do to time? Valuation methods give a structured way to price changes so both parties follow the contract instead of negotiating from scratch every time.

Most construction contracts set out the order of methods to use, starting with pre-agreed rates and only moving to more open pricing when necessary. Applying these methods consistently makes variation costs easier to justify, easier to audit, and far less likely to turn into a dispute.

Pre-Agreed Unit Rates

Pre-agreed unit rates use the prices already set in the bill of quantities or contract to value a variation. When the changed work is the same type as an existing item, you simply apply the agreed rate to the updated quantity instead of negotiating a new price.

This method is usually the starting point for valuing variations because it is quick, predictable, and easy to audit. It keeps the variation aligned with the commercial logic of the original contract.

In practice, pre-agreed rates work best when:

The varied work clearly matches an item already in the BOQ or schedule of rates

The original rates are still realistic for current market conditions

Both parties want a straightforward, low-dispute way to price the change

Day-Work Rates

Day-work rates are used when a variation cannot be fully defined or measured in advance, so the contractor is paid based on actual hours worked, materials used, and equipment deployed at pre-agreed rates. This approach is common for urgent, reactive, or investigative work, where the scope may change as hidden defects or site conditions are uncovered.

To keep day-work under control and defensible:

Require signed daily work sheets or day-work forms from the site, confirming labor, plant, and materials used.

Tie day-work rates back to the contract or tender, rather than negotiating them from scratch on every instruction.

Set clear rules in the contract for when day-work applies, so it is not used as a default pricing method for avoidable scope gaps.

Market Benchmarking / Quotations

Market benchmarking and supplier quotations are used when a variation introduces new work that is not covered by existing contract rates. In this case, the contractor prices the change using current market prices, vendor quotes, or subcontractor offers, and the quantity surveyor or cost consultant checks whether those figures are reasonable and consistent with the project’s commercial terms.

To use market benchmarking effectively:

Ask for multiple supplier or subcontractor quotations for significant variations, not just a single price.

Compare proposed rates with similar items already in the contract or recent projects to spot outliers.

Document all quotes and clarifications, so both parties can see how the final rate was agreed and revisit it if questions arise later.

Negotiated Lump Sum

A negotiated lump sum is a fixed total price agreed for a variation instead of building it up from detailed unit rates. It is often used when speed matters, the scope is relatively clear, and both parties prefer a single agreed figure rather than a line-by-line breakdown.

To make lump sum variations work smoothly:

Define clearly what is included and excluded in the lump sum, so there is no confusion later.

Record any assumptions about quantities, access, or sequencing that could affect cost.

Link the lump sum to specific drawings, specs, or method statements, so the scope is easy to verify if a dispute arises.

Cost Plus Percentage

Cost plus percentage is a valuation method where the contractor is reimbursed for actual costs (labor, materials, equipment, subcontractors) plus an agreed percentage to cover overhead and profit. It is typically used when the variation scope is uncertain or highly flexible, making fixed pricing difficult at the start.

Because the client carries more cost risk, transparency is critical. The contractor must keep detailed records of time sheets, delivery notes, invoices, and equipment logs so the client can see exactly how the final amount was built up.

To keep cost plus variations controlled and defensible:

Agree in writing which cost categories are reimbursable and what percentage markups apply.

Require contemporaneous records for all hours, materials, and plant charged to the variation.

Set up periodic cost reviews so overruns are spotted early, not at the final account stage.

Extensions of Time and Indirect Costs

Extensions of Time (EOT) deal with how a variation affects the project schedule and the contractor’s entitlement to more time. When a change disrupts critical activities or adds extra work, the contractor may be entitled to move the completion date and recover time-related costs.

Indirect costs sit behind that extra time. They include preliminaries such as site management, security, utilities, insurance, temporary facilities, and sometimes head-office overheads. If a variation extends the project, these costs usually rise even if the direct work on site looks modest.

To keep time and indirect cost claims credible and contract-compliant:

Link each EOT request to specific activities and a critical path analysis.

Separate direct costs (labor, materials) from time-related preliminaries in the breakdown.

Use contemporaneous records and updated schedules to show disruption, resequencing, or acceleration.

Follow notice periods in the contract so valid claims are not rejected on procedural grounds.

How FirstBit Helps You Take Control of Construction Variation Orders

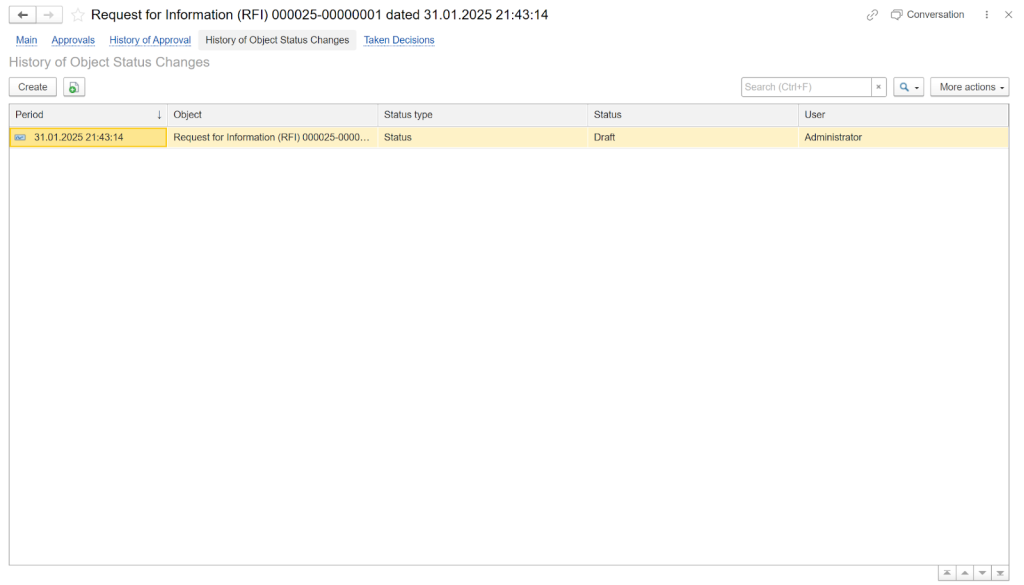

FirstBit ERP turns variation orders into a simple, repeatable process. Site engineers can raise potential changes directly from RFIs, material requests, or updated drawings.

The system routes each variation to the right approvers, applies value limits, tracks status in real time, and prevents work from starting before the variation is reviewed and approved.

RFI creation in FirstBit ERP

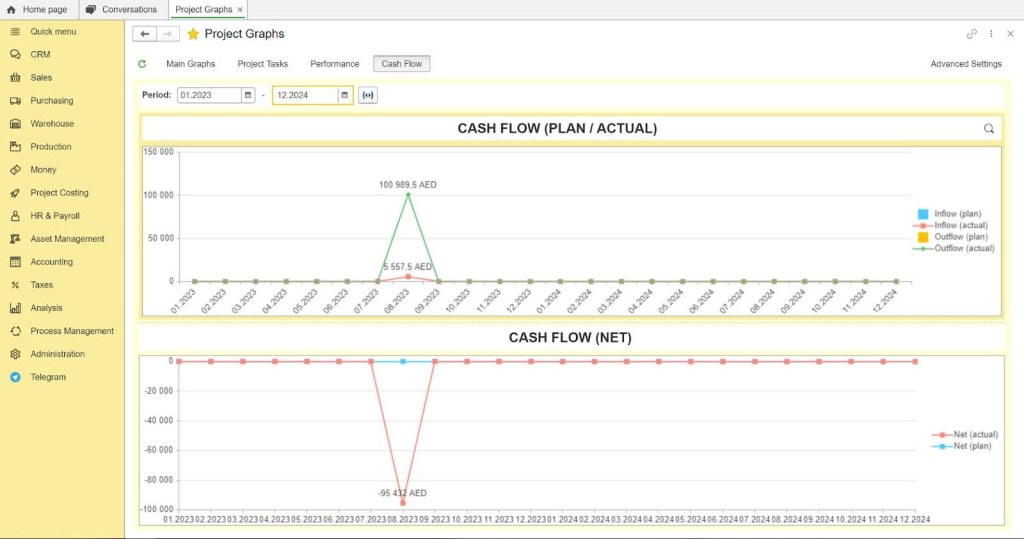

Every approved variation updates the project budget, commitments, and forecast automatically. In

FirstBit ERP you see how each change affects contract value, margin, and cash flow, along with any extension of time linked to that variation. This helps project managers, QSs, and finance teams keep a single, up-to-date view of cost exposure across all active jobs.

Cash flow tab in FirstBit ERP

FirstBit ERP stores all variation data in one place: scope descriptions, quotes, correspondence, approvals, revised drawings, and EOT records. Each variation has its own history, so you can quickly justify valuations, support payment claims, and resolve disputes.

This level of traceability strengthens internal controls and makes external audits or funding reviews much easier to handle.

Stay ahead of schedule

Control project timelines through FirstBit

Request a demo

F.A.Q.

What is an example of variation in construction?

A positive variation increases the scope of work, along with the project cost, whereas a negative variation reduces the overall cost. For example, removing several rooms from the floor plan before construction might lead to a negative variation.

What is variation in a project?

A variation is an alteration to the scope of work originally specified in the contract, whether by way of an addition, omission, or substitution to the works, or through a change to the manner in which the works are to be carried out. “In other words, variation meaning in construction is any approved change to the original scope, whether it adds, removes, or alters part of the works.

What are the causes of variation in construction?

Variations in construction often come from client changes, design adjustments, or unexpected site conditions, sometimes involving contractors. If not managed well, they can cause delays and cost overruns. To reduce their impact, contracts should outline how variations will be handled.

What are the advantages of variation order?

The benefit of variation order is to realize a balance between cost, function, and quality required of a project to the satisfaction of clients. Therefore, it will increase the value of the building. The variation clause allows an employer to pursue the aesthetic consideration in one project.

Anna Fischer

Construction Content Writer

Anna has background in IT companies and has written numerous articles on technology topics.